What’s the difference between UX and UI?

For any experience to truly connect with people, it must engage both halves of their brain. Now, we understand that this mythical separation of domain between the right and left hemispheres of the brain is more rooted in pop culture than science, but it is still an apt framework for this discussion. While some like to say UX and UI are two sides of the same coin, I think it’s more apt to call them two halves of the same brain. The analytical versus the aesthetic. The data versus the qualia. The objective versus the subjective. You get the idea. But what does that mean for how we might understand the individual disciplines themselves?

Left Brain, meet Right Brain.

For any experience to truly connect with people, it must engage both halves of their brain. Now, we understand that this mythical separation of domain between the right and left hemispheres of the brain is more rooted in pop culture than science, but it is still an apt framework for this discussion. While some like to say UX and UI are two sides of the same coin, I think it’s more apt to call them two halves of the same brain. The analytical versus the aesthetic. The data versus the qualia. The objective versus the subjective. You get the idea. But what does that mean for how we might understand the individual disciplines themselves?

Analogy time—UX is to architect as UI is to interior designer.

Let’s imagine the UX and UI designers of your digital design project are instead tasked with a bathroom remodel. The room is stripped to the studs. Without getting too graphic, we all understand that any bathroom must provide people with access to a number of critical functions. But the permutations of how the bathroom itself is laid out or how it appears, aesthetically, are virtually infinite.

The UX designer creates a blueprint.

In doing so, they will address some basic design questions. What goes where? How much space does each activity require? What should be closest to the door? Is there a logical flow from one area to the next? Should everything be visible the moment one arrives, or should some areas be obscured? How do we arrange water supply lines and drains to maximize utility while minimizing construction costs? Where do we need storage and with what do we fill it?

In UX design, the analog to that floor plan would be a wireframe. Wireframes are the blueprint. They document the structural design and how the experience is optimized and arranged to serve a predetermined set of goals or conversions. Wireframes are the graphical representation of the relative importance and hierarchy of elements, how those elements relate, what needs to be stored in those elements and what the logical flow should be between them.

The UI designer does the finish work.

If we’re staying with the bathroom analogy, the UI designer’s decisions dictate mostly how the bathroom feels. Paint colors. Material finishes. Fixtures. Sounds. Scents. At first blush, these seem superficial, but they actually make a substantive difference to how, or if, the experience elicits a proper response. So what does UI mean in our digital design world?

While the UX designer’s wireframes may provide broad guidelines as to what should appear on a screen and the interaction flow, the UI designer creates the actual screens, layouts, visual patterns and content and style guides that document the required family of UI elements like tone of voice, content length, buttons, icons, scrolls, menu styles, micro-animations, colors, typefaces, etc.

Both work best when considered and developed in tandem.

Of course, every digital property should work well and look and feel beautiful. But the best way to evaluate whether a design is successful is to understand whether or not it is achieving its objective. That objective may be to increase a business KPI (number of form fills, sales leads generated, etc.) or overall engagement levels like time on site, number of articles read, pages visited, etc. To maximize either, or any combination in between, requires a coordinated effort across all disciplines.

Consumer expectations for the quality of their digital experiences are increasing. Only by understanding and engaging with people logically, intellectually and emotionally will UX and UI professionals create a competitive advantage through design.

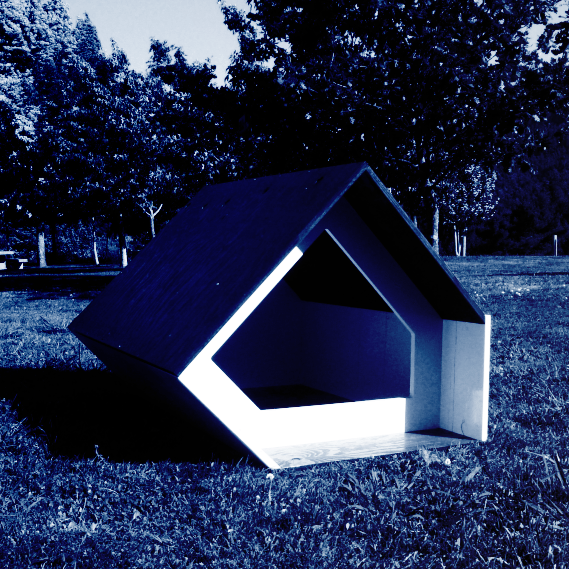

Tesla’s innovation is in the doghouse

Watching the world’s automakers respond (or not, as the case may be) to Tesla, has been interesting, to say the least. I find it fascinating to see an established market watch a competitor waltz in and secure a beachhead in a successful new category, with a near-zero response from the established powers for years.

And that’s a good thing.

Watching the world’s automakers respond (or not, as the case may be) to Tesla, has been interesting, to say the least. I find it fascinating to see an established market watch a competitor waltz in and secure a beachhead in a successful new category, with a near-zero response from the established powers for years.

All the while, the upstart works hard, establishes a brand, creates a supply chain and builds out proprietary charging infrastructure, not to mention (at the time of this writing) amassing the largest market capitalization of any US automaker. Even today, some of the largest, most advanced automakers are projecting they won’t be fully engaged in the electric market for another 2–3 years. So what does Tesla know that seems to baffle other automakers? Well, after having had the opportunity to drive a Tesla Model 3 for a few weeks, one thing hit me.

The difference between cats and dogs.

A genetic study of cats showed cats are basically unchanged from their feral ancestors. Meaning, they’re not technically domesticated. Well, they’re domesticated as much as they choose to be. And while people may derive a great deal of enjoyment and feel a great deal of empathy for their cats, the relationship isn’t in any way truly servile. In fact, it’s probably more accurate to say people are in service to the cats. Dogs, on the other hand, are the most genetically domesticated animal on the planet. And while not totally selfless, they are, for the most part, living in service to their owners. Why do I bring this up? Well, for almost a century, owning an automobile was more like owning a cat. It may be a rewarding relationship for many people, but ultimately, the human was the last consideration in the design, basically placed by the engineers into the mix in service to the machine. The car would do what it was asked, but it was, itself, never much help in the process. The innovation that differentiates Tesla is to design the car experience to be more like owning a trained dog. It’s a car in service to the driver.

Obviously, in that sense, self-driving comes to mind. But that’s not, in and of itself, what I’m referring to. Traditional automakers seem to start the design process by thinking about the machine itself—achieving a level of performance, adding a feature, etc. Tesla seems to have started at the experience and worked back to the machine needed to satisfy the vision for the experience.

For example, when the driver enters a Tesla, the car remembers and restores positions for the driver’s seat, driver’s sideview mirror and steering wheel steering mode, regenerative braking preference, mirror auto-tilt, instrument panel layout, performance preferences and all touch-screen display preferences, just to name a few. Pretty much anything you can set to your liking will automatically switch to suit you the moment you get into (or rather, your phone gets into) the car. The car adjusts to you.

When the car needs charging, not only will it remind you, it will show you where the nearest supercharging stations are, and, assuming you paid for the (inaccurately named) auto-pilot software, like a sled dog, will effectively assist you in getting there.

Enter the big dog.

The latest example of this perspective is the deeply polarizing Cybertruck. The first reaction most had to its unconventional design was of shock, even horror in some cases. However, when one considers the user experience as the main driver of the design process, a certain beauty emerges. The utility that the Cybertruck is poised to deliver is currently unmatched by any traditional truck maker:

Up to 14,000 pounds of towing capacity (tri-motor version)

120- and 240-volt outlets that can be used to supply power tools without the use of a generator

An onboard air compressor for tools

Adaptive air suspension

“The vault”: A motorized rollout cover that secures the bed; Tesla claims a solar-panel version should be available in the future, providing up to 15 miles of charge in a day

An innovative tie-down system that allows you to insert anchor or mounting points in various positions

Zero to 60 mph in less than 2.9 seconds (tri-motor version), 4.5 seconds (dual-motor) or 6.5 seconds (single-motor rear-wheel drive)

The whole announcement reminded me of a movie from the early ‘90s, “Crazy People,” starring Dudley Moore as an advertising executive in a midlife crisis. In the film, he pens what he considers an honesty-based headline for Volvo, which read: “Volvo: they’re boxy, but they’re good.” I have a suspicion Elon Musk would be quite happy with that headline, with perhaps the exception of wanting something more superlative, possibly incorporating a few well-chosen explatives in place of “good.”

I have a hard time imagining the Cybertruck coming out of the design shops of any of the major automakers. Though I also imagine those same automakers are having a hard time understanding how Tesla received more than 200,000 pre-orders for the vehicle within days of launch.

Empathy is an evolutionary advantage

Recent studies suggest empathy is what led to dogs being the most successful domesticated animal on the planet. And it seems that is what’s driving Tesla’s market success today. It will be interesting to see if the traditional automakers reveal themselves to be more akin to the dinosaurs or a pack of wolves waiting for their moment to pounce.

Corporate Innovation: Breaking Through Organizational Barriers

I’m not sure who first promoted the idea that the greatest determiner of whether a corporation could successfully innovate is an ill-defined, immeasurable quality named “agility.” I am sure that the individual in question had a penchant for oversimplification. Just do a search for “agile business” books on Amazon, and the results are well over the 2,000 result threshold where Amazon stops counting. It’s not that a company shouldn’t have the qualities linked to the idea of agility. It’s just that agility is an emergent condition resulting from a number of more easily quantified and measurable behaviors.

They say, “To innovate, you need to be more agile.” They’re oversimplifying.

I’m not sure who first promoted the idea that the greatest determiner of whether a corporation could successfully innovate is an ill-defined, immeasurable quality named “agility.” I am sure that the individual in question had a penchant for oversimplification. Just do a search for “agile business” books on Amazon, and the results are well over the 2,000 result threshold where Amazon stops counting. It’s not that a company shouldn’t have the qualities linked to the idea of agility. It’s just that agility is an emergent condition resulting from a number of more easily quantified and measurable behaviors.

Think of it this way. Asking or expecting a company with no history of innovating to be more “agile” is like asking or expecting a heretofore unexceptional basketball player to be more “LeBron James.” Whether we’re talking about corporate agility or athletic LeBronity, framing the end result as the starting point, is well, pointless. You need to work on improving individual skills—ball handling, footwork, free throws, offensive and defensive strategies, plays, etc.—until the subject exhibits skills that lend to an overall more LeBron James-like impression. But that analogy implies you have to do more work than simply decide to be more agile. Bummer.

But the good news is that once you understand the common barriers preventing most companies from innovating, it’s much easier to address those issues than it is to try to make any mere mortal into LeBron James. So, let’s start with the three most common organizational barriers to innovation—misaligned goals/incentives, unclear managerial vision and unsystematic evaluation of risk—and how to address them.

They say, “It’s never easy to turn a ship this size.” But it’s not the size that matters.

Before I get directly to talking about incentives, indulge me for a moment while I mix boating metaphors. All it takes to turn a ship, or a rowboat for that matter, is an alignment of forces. Rudders and thrusters. Arms and oars. While that kind of alignment is easier to envision for a waterborne vessel, the rules also apply to the business enterprise. The forces, however, are usually applied more indirectly. Okay, now let’s talk incentives.

If you do any cursory searches online on the topic of this post, you’ll likely find mention of another immeasurable quality that innovative companies must have—culture. But I’ll argue that just like “agility,” culture isn’t something you control directly. It’s something that emerges from the myriad behavioral incentives applied across every individual in the business.

For many businesses, the incentives that drive most employees’ behavior were formulated to maximize the output or efficiency of an employee’s individual business function as it looks today. And while that’s important, it can lead to intractable stagnancy, or waste, within the enterprise.

One of our clients, for example, spends well into the six-figures for their enterprise license for Salesforce.com. In theory, the sales reps should use Salesforce to catalogue everything they know about a lead or a live account. In theory, that data should be available to Marketing, Product Development, etc., to inform, drive or prioritize outreach efforts, product updates or innovation efforts. But, in practice, the sales reps don’t enter much or any data into the system.

The sales reps are incentivized by commission on sales only. And the most valuable currency in a competitive sales environment is customer/account information. The sales reps rightly fear that if they make their customer/account data accessible across the company, other reps could potentially steal their client. So, the reward structure, which in practice works well to maximize the output of the individual rep, has the unintended consequence of increasing customer opacity all around.

The solution? An equal and opposite force must be applied. The sales rep’s incentive plan should include some bonus based on the accuracy and completeness of his customer data. Further, the rep should be rewarded for the collective success of the sales department, the effectiveness of cross-sell marketing efforts based on the data they entered or the number of data-driven product innovations created by the product team, derived from customer profiles. Sales is but one example. You should review incentives across the board to uncover potential conflicts with innovation initiatives.

They say, “Management has no vision.” But it’s likely a language problem.

Not every decision an employee makes is a result of their incentive plan. Obviously. So, that means if we still want everyone steering the ship in the direction of innovation, we need to have guiding principles everybody knows and everyone can understand. There’s a chapter in my book, Innovate. Activate. Accelerate. that talks about how the language a company chooses to articulate their vision can have dramatic effects on their success in innovating. So, how can you ensure your own mission is at once descriptive, directional and inspirational enough to become the bedrock for an innovation culture? Ultimately, the rules boil down to this:

The mission should be aspirational

Often, companies develop mission statements with objectives that are satisfied entirely by their current offering, positioning the job in the minds of employees as “done.” For an innovation culture, it’s best to always keep the carrot at the end of a moving stick. Instead of asking to be great at what you do, ask for something as important as the transformation of the human condition.

The mission should be broad enough to encompass what’s yet to be created

The point here is that being a company that describes itself as offering “next-generation illumination for the world” provides more opportunity for adapting to new technologies than, say, describing the company as “leaders in incandescent lighting.”

The mission should glorify the pursuit of innovation itself

The pursuit of innovation is as much, or more, about taking risks, iterating, failing and discarding as it is about seizing the reins of the next successful new idea. This suggests the mission should, in kind, elevate the importance of the pursuit as much, or more, than any desired end.

They ask, “What’s the ROI?” But they should be asking, “How can we embrace and manage risk?”

We frequently hear from clients that unless they have a clear minimum guarantee of ROI, the company won’t greenlight a new idea. But innovation can’t be procured like office supplies. Risk and reward are the inseparable sides of the innovation coin. Of course, that means you need to embrace a culture of risk and acceptance of a certain level of failure. And, more importantly, what that level of failure could possibly look like before it occurs.

What makes an innovation culture work is that failures are measured, evaluated and learned from. The good news: There are more tools available now to model risk, even in highly complex markets. Machine learning, for example, can be used to evaluate customer and market data for previously unexposed correlations or motivations. Incredibly detailed, behavior-based, third-party consumer data can be purchased that can peel back yet another layer of the market onion. And, unsurprisingly, you have to do the math. But what should you be calculating?

Calculate the cost of innovating (The “I” in ROI)

You need to quantify what the financial investment would be in developing, launching, marketing and supporting the new venture—both initially and over time. That should include capital expenditures, facilities, technology, R&D, labor, IP (prosecuting patents, filing trademarks), etc.

Understand your market size

You can see a step-by-step breakdown of how to perform these calculations in another post on our blog: ““Math for Marketers: How to Evaluate Growth Opportunities””

Disruption factor (loss of existing revenue streams)

It would be nice to imagine that your disruptive solution would steal revenue from your competitors, but you should assume that any true innovation will be as desirable to your own customers. (See: The Innovator's Dilemma).

At some point, any truly innovative venture will bring with it a great deal of uncertainty—if it’s innovative, by definition, it’s not been accomplished before. And while it may be impossible to nail down exact returns, systematic examination of the risks should increase your chances not only of success but also of getting the green light to launch in the first place.

Even LeBron James wasn’t born as agile as LeBron James.

No one is born a great basketball player. It takes years of commitment. The same holds for companies seeking to become more agile. It takes commitment and practice over time.

Three signs of success that should make you want to innovate.

In business, we should always celebrate our successes. We should all find happiness and take comfort in classic, somewhat irrefutable, business metrics, like returning a healthy net profit, growing sales and customer loyalty, to name a few. But there are anecdotal success measures most people repeat that, while they directionally point to good things, should also have you start asking whether they actually are signs of a problem. Let’s look at three of the most common.

Success can be a double-edged sword.

In business, we should always celebrate our successes. We should all find happiness and take comfort in classic, somewhat irrefutable, business metrics, like returning a healthy net profit, growing sales and customer loyalty, to name a few. But there are anecdotal success measures most people repeat that, while they directionally point to good things, should also have you start asking whether they actually are signs of a problem. Let’s look at three of the most common.

There’s a line out the door!

We have all seen it. We have all said it. “That place is so great; there’s always a line out the door!” Is that a sign of success? Sure. For the most part. But it’s also a sign that there are potential improvements to be made in operations, service design or customer experience. I should add here that this is not meant to solely reference restaurants or retail. The idea can easily be seen as an analog to a situation like a general manager of a manufacturing business bragging, “Things are going so great, we can’t fill the orders fast enough.”

In either of these scenarios, despite the feeling of success, it’s likely that the business is, at best, leaving money on the table and, at worst, potentially creating a bad customer experience along the way. So, what should you look at if you experience this kind of success?

First, look at your asset turnover ratio. In other words, are you earning more revenue per dollar invested in the business today than you were before there was the proverbial line out the door? If so, success! If not, move on to step two—look for where you might have scale-related bottlenecks emerging. Does the additional throughput (people in line or orders entering the system) make each individual transaction less time- or resource-efficient? Can you simply not fit the resources you need to process those transactions into your current physical plant? Do your servers bog down due to too many simultaneous requests? Is your fulfillment staff simply overwhelmed? Of course, there may be traditional fixes like expanding the number or size of your locations/physical plant, hiring more staff or building up your technology infrastructure.

But it may be time to start asking a more foundational question, “Does my business have to work this way?” Can you change the layout of your physical location to improve flow? Can you imagine a service model that could increase your asset turnover ratio without any further investment in space or technology?

No one is complaining.

As noted Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde famously said, “There is only one thing in life worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” Another way to phrase that might be, “The opposite of love isn’t hate. It’s indifference.” Whether you’re running a retail operation, managing employees in a professional services firm or anything in between, if you find yourself in an environment where there are no complaints, it’s not usually because everything is perfect as it is. So, why the silence?

First, customers or employees may not be complaining because you might not be offering a safe, convenient or simple way to provide feedback. If the process feels too onerous, or if they feel like their complaints will be met with derision or indifference, there is little incentive to speak up. Second, and worse yet, it may simply be that your audience has become indifferent to your offering. So how do you know and what can you do about it?

In our experience, this is why every business should invest in ongoing customer-focused research. Understanding how customers (or employees) feel about their interactions with the company creates a better understanding of what’s happening today as well as a foundation of understanding upon which to innovate.

For example, you could develop a customer journey map that documents the touchpoints of your customer (or employee) experience as it currently stands. Done right, it shows how well, and how easily, your customers (or employees) are currently achieving their desired goals. And if they’re not, why not.

Outline (based on research, analytics, experience and expertise) what the customer is thinking, feeling and doing at each moment of interaction. Try to define how the level of satisfaction and happiness, or friction and frustration, fluctuate within the journey. Basically, identify low points, high points, joyful moments and trouble spots throughout the experience.

Only then can you truly know where and how to apply resources and innovate around your experience to transform indifference into engagement. Ironically, you’ll likely see complaints increase—along with accolades—as people become increasingly passionate about the experience you offer.

People spend a lot of time on your site.

If engagement with your web experience is good, more engagement is better, right? Well, maybe. Looking back to the “line out the door” section of this post, if increased time on your site correlates with increased transaction value, then, once again, success! But if the correlation is neutral or negative, it may be time to reevaluate the experience design. How would you start?

First, scour your analytics. Find out if (or where) the experience may be stifling visitors or impeding conversions. You’ll want to look for signs that people are stalled, confused or overwhelmed by choices. Do a significant amount of visitors spend time filling a cart, then abandon without transacting? Do they go through a process of gathering information but fail to download?

For a more literal understanding of those behaviors, you can also use tools like CrazyEgg and Lucky Orange. CrazyEgg provides heat maps that let you visually assess where visitors are engaging and for how long. Lucky Orange lets you actually watch recordings of visitor behaviors. For example, if you received a form fill, and you wanted to better understand that visitor’s journey from initial landing on the site to filling out the form, Lucky Orange will actually let you go back, DVR style, and watch their session. These tools can build a story about your visitors and what they’re really accomplishing, or not. Once you know that story, it should be easier, if not obvious, what interactions need to be redesigned or re-concepted altogether.

The best of times is the best time to innovate.

Everything we talked about in this article falls into the category of good problems to have. But as any innovator can tell you, the most fruitful place to start on any transformative innovation project is by looking at the best-in-class solution and asking, “Could this work better?”

The three most important trends in health care experience design for 2019

Over the past 30+ years, Magnani has had the pleasure of working with clients across a variety of industries—from health care to hospitality, industrial equipment to medical devices, household cleaning products to sporting goods, dining cruises to the world’s most highly traded financial derivatives contracts, just to name a few. Each engagement has broadened our collective perspectives while confirming one underlying truth: Regardless of emerging trends, ongoing changes in technologies or the idiosyncrasies of individual markets, the fundamentals of human nature remain constant.

We’ve seen 30+ years of shifting trends. And one underlying constant.

Over the past 30+ years, I’ve had the pleasure of working with clients across a variety of industries—from health care to hospitality, industrial equipment to medical devices, household cleaning products to sporting goods, dining cruises to the world’s most highly traded financial derivatives contracts, just to name a few. Each engagement has broadened our collective perspectives while confirming one underlying truth: Regardless of emerging trends, ongoing changes in technologies or the idiosyncrasies of individual markets, the fundamentals of human nature remain constant.

While we are continually working at the forefront of experience design trends, we believe the inspiration for real innovation comes from respecting those trends but also, more importantly, looking to find a deeper understanding of the foundational human motivations fueling them.

To that point, there are three fundamental elements that drive all trends—basic(human) needs, drivers of change (shifts in technology adoption, population changes, etc.) and innovation (newly available tools or methods). But it is perhaps more accurate to say that motivation stems from the tension occurring at the intersection of those forces.

To understand those intersections, we rely on a variety of resources and quantitative and qualitative research methodologies, from ethnography to focus groups, individual interviews, secondary research reviews and data analysis.Further, depending on the scope and time horizon of the project, we may utilize tools such as the trend framework, consumer trend radar or consumer trend canvas. We also consult market research reports and publications from organizations like MINTEL, Kantar, IRI and Nielsen, among others. Ultimately, we design research and analysis strategies and plans that are unique to every project, challenge and budget.

As survey the greater market environment, we see the dominant customer experience trends, regardless of industry category, surround three main thematic pillars: consumer control, data ethics and privacy and automation/personalization. In health care specifically, we must layer onincreased demand for access to care, the democratization of health information and the drive to lower costs (from both the consumer and provider sides of the equation). Specifically, in health care, we see these trends expressed in the following ways:

Consumer Control:

Consumers expect health care experiences to be as frictionless and simple as hailing an Uber … sort of.

Consumers want access to health information and care whenever and wherever they need it.But there’s a catch. While consumers are increasingly expressing the desire to manage their own care, the technologies that enable that control have varying levels of adoption among different generational cohorts. For example, newly available telemedicine solutions that should, in theory, provide increased levels of control and access, have varying degrees of acceptance depending on age and generational and conditional differences. To state it more colloquially, the older and more informed the patient, the less likely the patient is to prefer a technology solution over consulting a physician directly.

Simultaneously, consumers want increased transparency and choice, ostensibly in order to more actively shop for their best care options and control costs. However, it has not been shown that lower cost and improved proximity are as powerful an influence over care decisions than a physician referral.

In short, currently, control-enabling technology is best suited to enhancing personal connections in a health care journey, not replacing it. But that balance should move more toward the replacement side of the equation, as the balance of the population shifts to younger generations.

Data Ethics and Privacy:

Data privacy issues are moving beyond HIPAA.

For perhaps the first time, general concern over data privacy is on the consumer radar. Thanks to HIPAA, privacy rules surrounding traditional medical records and health information are clear and established (albeit under constant review). But the entrance into the market of consumer fitness- and health-related technology companies is creating a new privacy gray area for consumers and health care companies, alike. Quasi-medical devices, like sleep and fitness trackers, heart rate monitors and fitness trackers, while creating a compelling feedback mechanism for consumers, are a vector for data leaks and privacy violations. These products and the data they create should enable a more holistic, long-term understanding of patient well-being and enhance the customer experience. But health care providers and organizations need to be aware of vulnerabilities and create increasingly secure integrations.

Further compounding data privacy issues is the increasing role of caregivers. It’s been estimated that there are more than 40 million family members acting as unpaid caregivers in the U.S., and the number may increase in the coming decade. Among the many challenges in creating a seamless health care experience, a significant challenge arises around allowing caregivers to provision access and permission for personal health information and electronic medical records while respecting the patient’s privacy and security.

Automation/Personalization:

In health care, every patient represents a distinctive market of one.

Health isn’t a simple product or service that can be transferred to a consumer. Each consumer is physically and emotionally unique. Therefore, there is no all-things-to-all-people solution to providing the optimal customer experience.The industry will need to use emerging technologies to provide the right experience for each customer, based on that customer’s needs at any specific point in time. No small challenge, especially given the privacy restrictions mentioned above.

Thankfully, technologies for privacy-compliant extreme personalization are advancing rapidly. We foresee technologies like blockchain increasingly supporting interoperability and personalization while maintaining sufficient control over data leakage. Ultimately, the trends suggest patients should realize higher-quality care experiences such as blockchain and competing crypto-technologies allow seamless sharing of medical records across health care providers while maintaining privacy and control.

The success factor no one talks about in Presidential debates.

As early 2020-election-season rhetoric swells to a roar, obviously the future of health care is a large part of the stump speech for every candidate. All of the candidates talk about the broad brush economics of how a change in the way we as a society pay for health care might affect our pocketbooks (not to mention our individual survival). What you don’t hear is how we might really improve the health care experience beyond cost and basic access. Whether or not we will see universal health care implemented, equal consideration should be given to the quality of the experience itself as will be given to how the money changes hands. That’s surely where the long-term successes or failures of any future system lies.

What is ASMR? (And should your CX team care?)

Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR) refers to a tingling, or at least pleasant, sensation some people feel when they hear what can be best described as soft scraping, tapping or rustling sounds. Most commonly, those sounds are something like the gravelly sound of a whispering human voice, two sheets of paper slipping past each other, soft tapping on a something hollow, a plastic bag being crumpled or just about anything similar that is recorded through a microphone placed extremely close to the sound source. But ASMR can also be triggered by something tactile, like peeling the protective plastic off of a brand-new television screen, or visual by the movement of hands or lips.

ASMR: a tingly whisper banned by the Chinese government.

Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR)refers to a tingling, or at least pleasant, sensation some people feel whenthey hear what can be best described as soft scraping, tapping or rustlingsounds. Most commonly, those sounds are something like the gravelly sound of awhispering human voice, two sheets of paper slipping past each other, softtapping on a something hollow, a plastic bag being crumpled or just aboutanything similar that is recorded through a microphone placed extremely closeto the sound source. But ASMR can also be triggered by something tactile, likepeeling the protective plastic off of a brand-new television screen, or visualby the movement of hands or lips.

For some (not me, admittedly) it’s purported to be audiovisual bliss, delivering an opioid-like rush to the listener/viewer—perhaps it’s the other side of the nails-on-a-chalkboard coin.In any case, the explosive growth of content tagged with #ASMR on social video sites has led to a lot of questions about its triggers, benefits, risks and long-term social impact. And, as mentioned in the header of this section, theChinese government became so concerned, it banned the posting (or at least tagging) of ASMR videos entirely over concerns that the content was pornographic. Which, I have to assume, means someone in the Chinese government really enjoys ASMR videos.

How popular is ASMR?

A Google search for the term “ASMR video” returns more than 98 million results. Digging a bit deeper into GoogleTrends, we see interest growing at an accelerating rate globally. Obviously, there’s a great and growing segment of the population who (unlike me) are finding a deep connection to the subject matter.

So, what are the economics of ASMR?

With more than 640 million views, the leadingASMR channel on YouTube (only one of many), gentle whispering, reportedly generates more than $500,000 in revenue annually. Given those numbers, you likely wouldn’t be surprised to discover that several brands have jumped onto the very quiet ASMR bandwagon.

During the 2019 Super Bowl, Michelob Ultra debuted a commercial featuring Zoe Kravitz whispering, scraping, tapping … you know, all the ASMR things, with a bottle of beer. The idea was to create for consumers a physical experience at a distance.

IKEA did a bit of ASMR homework and produced “Oddly Ikea,” a25-minute-long commercial, featuring the sounds of hands gently caressing some crisp, new bedsheets, dragging along a comforter, rustling clothes on hangers in the closet and the like. At the time of this writing, it has garnered more than 2.6 million views.

If you take a moment to Google ASMR ad, you’ll find somewhere near 100million results. Obviously, the Mad Men have discovered its pull. But what about a more esoteric application in customer experience design? Let’s investigate.

Adding ASMR triggers to UX design

Sound is generally overlooked by most UX designers. But careful use of audio feedback can provide a much richer and more intuitive user experience. And, when considering specific ASMR triggering sounds, one should assume, a more physically satisfying experience. The movement of a mouse or the dragging of a finger across a mobile device may be perfect moments to add a soft scraping sound. Add a soft tapping sound to wait screens? It seems better than a spinning rainbow beach ball. And let’s not forget the possibility of leveraging visual ASMR triggers. Instead of a static portrait of a model, why not a silent shot of that model mouthing a few choice phrases. An interesting potential example of this (and I am unsure if ASMR was the intent) might be answerthepublic.com. From the beard to the big wool sweater to the continuous movement and mouthing of words, it seems like no coincidence.

answerthepublic.com home page

Adding ASMR triggers to physical experiences

Even the most dyed-in-the-wool online businesses are creating physical retail experiences. Warby Parker, CasperMattress, Indochino—even Amazon. With the ASMR trend in kind, it may be time to eschew smooth polished surfaces and incorporate a bit more sand-like texture on checkout counters. Perhaps rustling layers of cellophane between items of clothing and their hangers. Or, punctuating the store experience with extended soft bursts of compressed air. A bead/pellet fountain? I guess I’ll leave the specifics to interior designers who, unlike myself, can actually experienceASMR.

So, you can. But should you?

I wouldn’t consider invoking ASMR for ASMR’s sake, good experience design or smart branding, per se. Every expression of your business and the design of every connection with a customer is to be considered in the full context of your positioning and your goals. However, there's no reason ASMR shouldn’t be one more tool in the experience design toolbox. All other conditions being equal, why wouldn’t you want your customer to be pleasantly tingly inside?

Link: